Stress is a strange phenomenon, a signal that indicates to your body something is threatening your life and you need to do something about it immediately. As cave-dwelling Homo sapiens, stress looked like animals trying to eat you or not finding enough water to survive. Today, our stressors are not always life-threatening, but our bodies don’t know the difference. In Part I of our hormone optimization series, we discussed the major structures of the endocrine system and which hormones are responsible for what body functions. This week, we’ll zero in on the complex feedback loop that strives to keep you safe, the role of cortisol, and what you can do to reduce the negative effects of prolonged stress on your health.

Jack just opened a restaurant. Though he’s worked in restaurants for most of his adult life, this is the first time he’s owned his own business and taken on all the stress that comes with it. There are employees to manage, orders to make, bills to pay, and a slew of customers to win over.

As Jack walks around the restaurant, he thinks about all the things that could go wrong. The cook could quit. The food could be spoiled upon arrival. The waitresses could be stealing money. The customers could be unsatisfied with their experience.

Jack’s brain processes these imaginary events as reality. It doesn’t completely distinguish between perceived danger and actual danger. As a result of millions of years of human evolution, Jack’s body prepares itself for stress the only way it knows how- activating the HPA axis.

Role of the HPA Axis

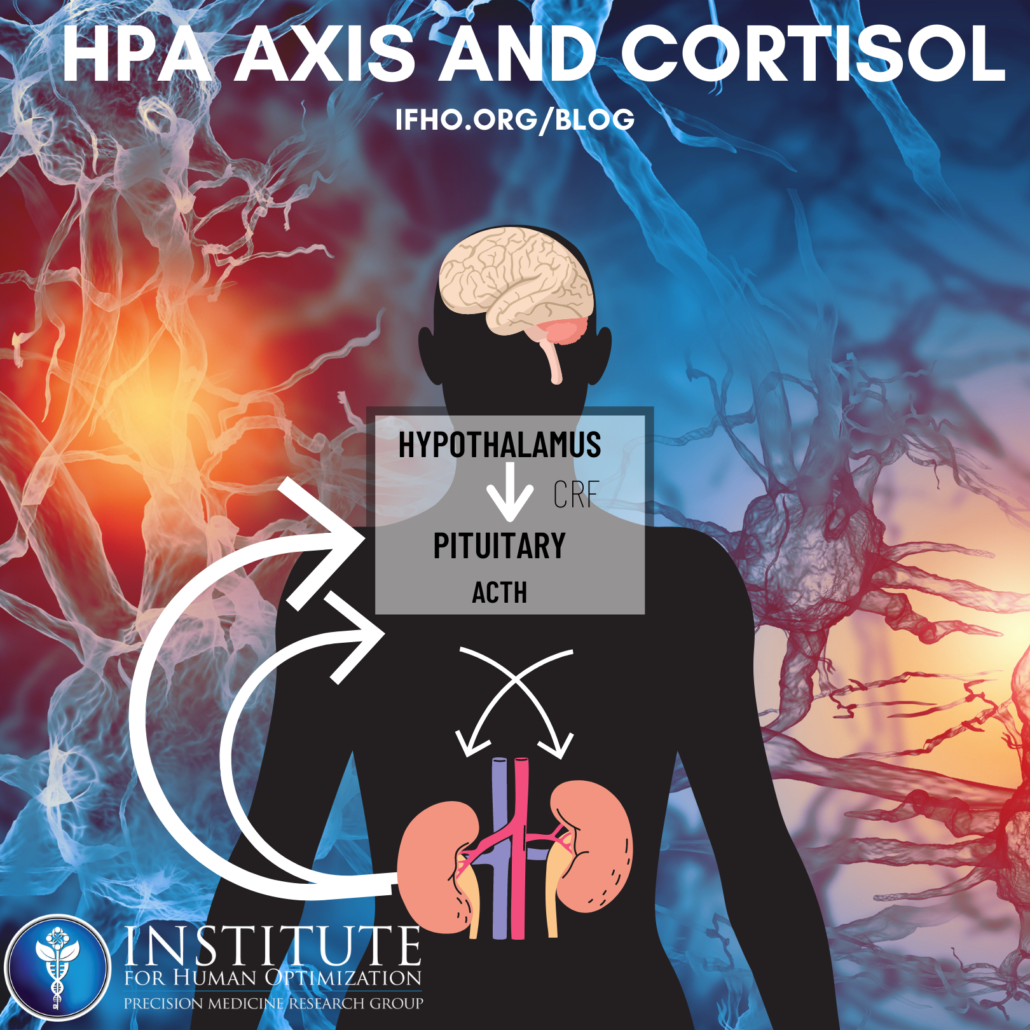

The HPA axis is a feedback loop that regulates your reactions to stress. Specifically, it links the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenals- all vital parts of the neuroendocrine system.

The loop begins when something stressful happens- one of the waitresses at Jack’s restaurant gets ill in the middle of the busiest shift of the week. As soon as Jack hears the news, his sympathetic nervous system is activated. Epinephrine and norepinephrine are released, the hormones responsible for the “fight-or-flight” response we once used to run from saber-toothed tigers.

With these hormones released, Jack’s HPA axis is in full swing. His hypothalamus (a small part of the brain concerned mainly with keeping the body in a state of homeostasis) secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) into his bloodstream. In the brain, CRH increases feelings of anxiety and temporarily improves Jack’s memory and selective attention. He’ll need his brain in an attentive state to deal with whatever stressor he’s facing.

CRH is a message to the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) which travels to the adrenal cortex like a letter traveling to your mailbox, binding to adrenal receptors, and causing the final section of the loop- the secretion of cortisol, the “stress hormone”.

Role of Cortisol

As the night goes on, and more inevitably stressful events occur, Jack’s bloodstream becomes inundated with cortisol as his adrenal cortex pumps out the hormone a little at a time. Cortisol’s main job is to release glucose into the bloodstream to be used as instant fuel for either fighting or running from his problems. Each pump results in about fifteen minutes of sustained cortisol release.

Cortisol also helps shut down secondary functions like sexual desire and urinary urges. You wouldn’t want to have to pee while running for your life or fighting an enemy and Jack is able to cover the waitress’s entire shift without having to use the restroom.

Unfortunately, Jack’s stress does not end after the difficult shift. He carries the weight of the night home with him and wakes up to another day of difficult obstacles. Each event re-actives the HPA axis and starts the whole process over again, inevitably leading to elevated cortisol levels for long periods of time.

Many studies show this kind of chronic stress is not beneficial for longevity and overall well-being:

“It appears that being exposed to stress can cause pathophysiologic changes in the brain, and these changes can be manifested as behavioral, cognitive, and mood disorders (Li et al., 2008). In fact, studies have shown that chronic stress can cause complications such as increased IL-6 and plasma cortisol but decreased amounts of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is very similar to what is observed in people with depression and mood disorders that exhibit a wide range of cognitive problems.”

Yaribeygi, H., Panahi, Y., Sahraei, H., Johnston, T. P., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI journal, 16, 1057–1072. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2017-480

If Jack is constantly bombarded with cortisol, his immune system is constantly suppressed. This leaves him vulnerable to disease and inflammation that can be detrimental to the body over time.

Cortisol also activates the autonomic nervous system, indirectly affecting the cardiovascular system. Jack’s heart rate increases, his muscles tense and contract, and blood flow is diverted from his organs to parts of his body that will help him fight or run. Again, this is all fine for a short period of time, but the organs need blood flow to operate correctly.

In addition, his hippocampus is extremely sensitive to stress and also responsible for the conversion of short to long-term memory. Animal studies show that a chronic state of stress can cause a reduction in the accuracy of spatial memory and negatively affect learning. Temporarily, Jack is sharper and better able to handle his environment. But over time, this kind of attention is not sustainable, and his brain physically begins to change to compensate for the abundance of cortisol.

How to Manage the HPA Axis and Cortisol

If you can understand how your body works, you can learn to work with it instead of against it.

If Jack wants to avoid the problems caused by an overactive HPA axis, he must start with what triggers the feedback loop in the first place- stress.

It isn’t an option for Jack to sell the business he worked so hard to acquire. Even if he did, he’d still have to deal with the stressors of modern life- finding new work, paying bills, handling family life, driving at speeds of 60mph on a daily basis, and anything else that comes up.

Eliminating stress is not possible and in short bursts, it’s not even harmful. It is the chronic, constant stress that slowly erodes our body functions and mental well-being.

Jack understands it is not the elimination of stressful situations, but how he deals with them that matters. He begins to implement the following lifestyle hacks to counteract the effects of cortisol and minimize the stress he feels from work and life:

- Practice good sleep habits.

Studies show a clear connection between sleep and cortisol levels. Not getting enough quality sleep affects you in all aspects of your health and being groggy during the day can cause more stressful situations to occur. Aim for 7-8 hours with little disruptions. Going to bed at the same time each night helps regulate the chronobiome and cortisol levels. - Exercise.

A recent study had young participants perform moderate aerobic exercise three times a week and tested their cortisol levels via saliva. Interestingly, the study found that exercise increased cortisol levels initially following the workout to deal with the stress, but over a course of four weeks, their overall cortisol levels decreased. Many people report being exercise being beneficial for their mental state, helping them make more clear decisions and better able to regulate their emotions. - Practice meditation or mindfulness.

Unfortunately, there haven’t been many large scale studies on the effects of mindfulness (focusing on being in the moment and doing things intentionally instead of letting your mind race on autopilot) on the HPA axis.

Recently researchers did use a mediation retreat to test subjects’ cortisol levels before and after meditation as well as before and after the retreat as a whole. They did find that cortisol levels were decreased, but without another control group, the results are not unquestionable. However, it makes sense that quieting the mind and focusing on the moment would create less stress, and as a result, lower cortisol levels.

Jack strives to focus on one task at a time and notice when his mind begins to worry about things he can’t control or things that happened in the past. Our bodies don’t understand the difference between a perceived threat and a real one and secrete cortisol either way. - Have fun.

Jack’s business is important to him, but he understands that a balance must be struck if he’s to live a long and healthy life. He begins to make time for things he enjoys and doesn’t stress him out. He goes fishing on the weekends and hangs out with his family. If he finds himself feeling stressed at work, he makes a conscious attempt to put on music that makes him happy or make a joke about the situation to lessen the tension.

If your mind perceiving stressful situations is what stimulates the HPA axis, then by changing the way you feel about the situation can help dramatically. Viewing obstacles as challenges, shifting your thoughts to ones of gratitude, and laughing all help to naturally lower cortisol levels. So make stressful things into fun things.

At the Institute for Human Optimization, we recommend our patients receive a hormone panel to get an idea of how their body is handling daily stressors. We take an integrative approach and aim to give people practical lifestyle hacks that can lower their cortisol and reduce the likelihood of diseases that occur as a result of chronic stress.

For more in-depth information on how to hack your health, check out Dr. Anil Bajnath’s book, “The Longevity Equation” or schedule an appointment with the Institute here.